First application of the Glawischnig-Piesczek CJEU decision

As reported, the CJEU clarified in the Glawischnig-Piesczek decision (C-18/18) the possible scope of injunctions against host providers such as Facebook. Following this decision courts may order the deletion not only of the specific infringing post but also of all information with equivalent meaning, even if it originates from other users.

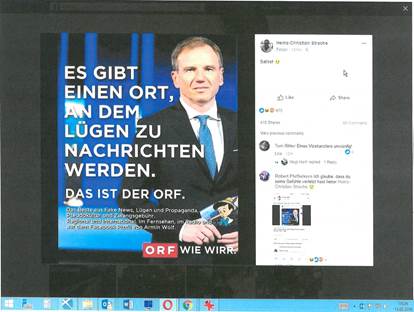

In a new and unrelated case (4 Ob 36/20b), the Austrian Supreme Court (OGH) applied these principles for the first time and issued a remarkably broad injunction. The Austrian Broadcasting Corporation (ORF) acted as plaintiff against defendant Facebook. The dispute concerned the following picture of an ORF news anchor, to which an Austrian politician had added a text translating to: “There is a place where lies become news. This is the ORF”:

The decision by the Austrian Supreme Court

In preceding civil and criminal proceedings based on defamation against the politician and his party, courts already ordered the deletion of the picture from the specific accounts. However, as the image continued to appear in various Facebook groups, ORF requested Facebook several times to delete these posts as well. However, Facebook refused and the ORF filed a lawsuit, which was based both on the ancillary copyrights to the photograph and on infringement of personality rights of the ORF under § 1330 Austrian General Civil Code.

Confirming the previous instances, the OGH granted the complaint and issued two injunctions:

- Facebook was no longer allowed to spread the image without consent of ORF and

- Facebook had to refrain from “distributing the allegation that the plaintiff is turning lies into news or other allegations with an equivalent meaning.”

Both injunctions oblige Facebook to delete all infringing content regardless of the user posting it. This alone creates an obligation for Facebook to monitor all content.

Moreover, the second injunction concerns not only the original allegation, but also all equivalent statements. Importantly, in the decision grounds, the OGH defined what is meant by equivalent und thus further specified the criteria set by the CJEU:

The CJEU itself had defined equivalent information as information “conveying a message the content of which remains essentially unchanged” (C-18/18, margin no. 39 and 40). However, equivalent information must contain “specific elements” that enable the host provider to use automated search tools for deletion. Hosting providers furthermore cannot be obliged to make an independent assessment (C-18/18, margin no. 45 and 46). Yet, this emphasis on the similar meaning on the one hand and the possibility of automated, computer-aided recognition on the other hand created a potential contradiction. Machines cannot yet (sufficiently) grasp the meaning of words and “specific elements” (such as the name of a person) can have a completely different meaning in a different context.

On the backdrop of this tension, the OGH decided entirely in favour of the “same meaning” and drops the criterion of machine-based recognisability. According to the OGH, this is permissible under EU law, since the Member States have particularly broad discretion in implementing the relevant E-Commerce-Directive (EU Directive 2000/31). Furthermore, the only limit for injunctions is that they may not lead to a general obligation for host providers to actively search for illegal content; the possibility to use automated techniques can therefore not be decisive.

According to the OGH, information is equivalentif a “core conformity” is apparent for a (human) layperson at first glance or can be established by technical means (e.g. filter software).[1]

This definition may pose a major task for Facebook. There are thousands of comments on the Facebook pages of the ORF alone. It is not hard to still find comments among them accusing ORF of spreading “fake news” and the like. For a layperson, many of these comments would probably be equivalent in their core to the accusation that the ORF turns lies into news. This raises the question whether Facebook already violates the injunction and if the ORF could therefore request a coercive penalty, which can reach up to € 100.000,- per day.

Coercive penalties under Austrian law require the fault of the defendant, which therefore must have had the opportunity to prevent the infringement and negligently or intentionally failed to take advantage of it.

To avoid penalties, Facebook must therefore make all reasonable efforts to prevent the dissemination comments covered by the injunction. But what are reasonable efforts for Facebook?

Applying a strict standard, one could see a violation already in the moment an infringing comment appears on Facebook. To avoid penalties, Facebook would have to check every post before it is published. Since no filter software is perfect, this control would have to be carried out by a human at least in some cases. Such control would put a major burden on Facebook. However, some online forums – such as those of Austrian daily newspapers – do rely on a pre-publication check.

However, in the author’s opinion, in view of the danger of censorship through overblocking, one should acknowledge the limitations of the platforms and deny liability for (more or less) isolated or only briefly visible posts.

Which model Austrian and ultimately European courts will choose will have a significant influence on how Facebook and other social networks will have to design their platforms.

Territorial scope of the injunction

According to the CJEU, the Member States may determine which territories are covered by injunctions. A worldwide obligation to delete infringing comments is therefore not contrary to EU law.

In the case at hand, however, the OGH issued an injunction for Austria only. Facebook therefore does not need to delete the content completely, but merely has to use geo-blocking to block access for Austrian users. Concerning ORF’s claims based on copyright, the OGH justified this with the principle of territoriality in intellectual property law.

However, this does not apply to the protection of personality rights. Such rights are generally not territorially limited. In principle, injunctions, for example against insulting content, may therefore have worldwide scope. According to Austrian case law, however, the plaintiff must request this explicitly. Since ORF failed to do so, no worldwide injunction could be issued.

Based on its personality rights, however, ORF could very well apply for a worldwide injunction in a new complaint.

[1] Remarkably, this definition also includes information that does not have the same meaning for a human layperson, but does for a computer program.