The artificial intelligence Dall E 2 generates controversy. Photographers, illustrators and designers feel threatened, because with Dall E 2, images can be created by text input. Uncomplicated and but with open legal questions.

What is Dall E 2?

Dall E is an artificial intelligence developed by OpenAI. OpenAI describes itself as an AI research and deployment company and says about itself:

OpenAI’s mission is to ensure that artificial general intelligence (AGI)—by which we mean highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at the most economically valuable work—benefits all of humanity.

The company seems to have succeeded with its new product Dall E 2. Because Dall E 2 generates images within seconds based on simple text input in impressive quality, in different styles and with a creative approach.

The problem? Dall E 2 puts further pressure on the precarious group of creatively active people by surpassing the artistic and craft skills of people.

But how does Dall E 2 work?

The AI works through text input. Users can describe the desired images in short and simple text, and the AI presents visual interpretations of these text inputs. If one of the images is suitable, users can edit it further until they are satisfied with the result:

For a technical description of Dall E 2, we refer here to an excellent article by Alberto Romero

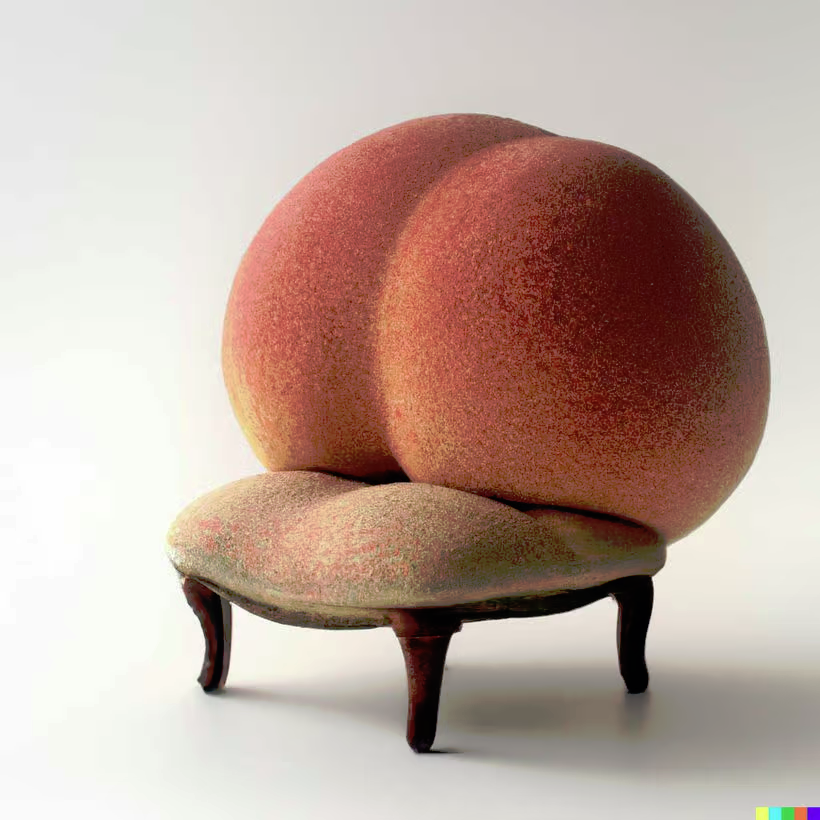

Example:

“an armchair in the shape of a peach”

But of course it can also be more complex.

Another example:

“A full-body statue holding a computer sitting at the edge of a pool in a roman bath. Marble, copy after Hellenistic original from ca. 200 BC, hyperrealism.“

Fantastic, we think to ourselves! Do you too? Whimsical and exciting throughout. But in recent weeks, critical discussions about Dall E 2 and its implications/consequences have emerged in the mainstream media.

Who criticizes the use of Dall E 2 and why?

Some people fear a threat to creative workers, and probably rightly so. However, creative industries have always worked notoriously in precarious conditions within the framework of the economic exploitation of their services. If the services cannot be charged for, they are worth nothing. And Dall E 2 fits this perfectly because AI is fast, versatile and cheap in creating content.

These advantages are especially beneficial for magazines, newspapers, digital platforms and advertising purposes, where photos and illustrations are used decoratively and for short periods. Where stock photos were used in the past, Dall E 2 images now find their place.

The – at least current – legal situation also facilitates handling because these works have no creator from today’s legal perspective. The creator is “the machine”, i.e. the AI – most legal systems so far provide that only a human being can be the author of a work and enforce these rights. The results of Dall E 2 are, therefore, automatically in the public domain.

Even renowned magazines like “Cosmopolitan” or “Economist” have used AI to design their covers. The AI hype is spreading. Whether it will lead to a lasting change in media design remains to be seen.

Looking at the existing stock photos market, one could welcome the market mixing up by Dall E 2. Finally, an exciting alternative that you can design yourself. Inexpensive and inspiring.

The quality of mass-produced stock photos tends to be poor, banal in content, lacking aura and life – and thus often unusable – and did not primarily help creators to succeed, but, if at all, the providers of the platforms themselves.

This is not the only reason why Dall E 2 could be seen as a complement rather than a threat. Dall E 2 does not represent serious competition for creative artists because, in the end, creative power does not equal artistic craftsmanship. Any computer can reproduce a Venus de Milo, but the idea and the time of its creation make it unique.

The fear of some production-oriented designers or illustrators is nevertheless quite understandable. After all, the cannibalization of craftsmanship by emerging technologies is not a new trend, and what Dall E 2 offers today is probably only the beginning.

Morality in the context of artificial intelligence?

Inevitably, however, a technology like Dall E 2 brings with it not only changes in production technology but also moral implications.

By defining visual content, the AI makes moral choices. For example, by producing images, the AI sets stereotypes of gender classifications and determines what evil, sound, and sexually legitimate mean. Dall E 2 evaluates and gives sense in the context of the options OpenAI allows.

An example:

“a beautiful man sits in a red chair and drinks a coffee, painting”

So why does Dall E 2 create this man? Why is he white? Why does he have a three-day beard? Why does he have tousled hair? Why is he in his 30s? Why is he sitting on that chair design? Why those pants? And why a V-neck? All these questions remain unanswered. Open AI’s norms and, thus, the company’s views and values remain invisible in the background.

Open Ai comments:

Our content policy does not allow users to generate violent, adult, or political content, among other categories. We won’t generate images if our filters identify text prompts and image uploads that may violate our policies. We also have automated and human monitoring systems to guard against misuse

In addition, Dall E 2 allows deep manipulations of already existing images of people. For example, the software can help fit their head onto a well-toned male body or the model dimensions of a 16-year-old. And it does so quickly, easily and relatively perfectly.

Example:

Upload: Philip Reitspergers Kopf | Text: WWE wrestler

Artificial intelligence can change an individual’s identity and dignity by swapping backgrounds and adding or manipulating body parts. However, the AI does not check the consent of the person depicted but assumes permission is given. OpenAI only protects itself in its terms of use.

Example:

Upload: Philip Reitspergs Kopf | Text: Laocoon and His Sons

Dall E 2, a creative tool?

For all the legitimate questions – Dall E 2 is here to stay and is not the only product on the market. Its use will lead to a shift in the balance of power in creative visual content creation.

In particular linguistically educated people who have not deepened their visual skills can now independently create and adapt images. Of course, the more and more precisely a human can communicate something to the AI through textual input, the better and more interesting the result will be. However, the path from text to image also leads to new possibilities for visually trained humans.

A tool of research.

By generating a pool of visual content on a topic, Dall E 2 is a fantastic tool for aesthetics and content. Furthermore, the interpretations of AI, combined with humans’ creativity, create new explorative possibilities.

A tool for inspiration.

Dall E 2 can equally be used to get inspired. By generating interpretation, adaptation and synthesis of already existing but also new textual content, the AI creates a multitude of starting points in no time at all, which are undoubtedly different from the analogies of one’s thought processes and can thus lead to new ideas. In particular, Dall E 2’s misinterpretations of content and aesthetics are often enriching.

A tool for finding materials.

When creating material collections, Dall E 2 is a great help. By entering text, visual collections of materials can be created, combined and synthesized in further processing and whose use is legally free, at least at first glance. Yet, it remains to be seen whether Dall E 2 will keep enough distance from its “sources of inspiration”, should the author of an underlying work object to disseminating a result of Dall E 2 – see below on the legal issues

A tool for finding the future.

According to Open AI, AI is successfully used to imagine future visual possibilities: “A reconstructive surgeon told us that he’d been using Dall-E to help his patients visualize results. And filmmakers have told us that they want to be able to edit images of scenes with people to help speed up their creative processes.

A replacement for image editing programs.

Dall E 2 also offers an “editor” mode in addition to the picture exhibition. This allows you to combine images while the AI independently generates and adds missing content. Top image editing brands would probably wish for a feature in their programs because this goes far beyond the aesthetic, content-dependent filling of areas.

Dall E 2 offers more than fancy pictures for little money. The use cases described merely reflect our scope of application with AI. Other people and companies will find more usable models—one exciting thing.

Dall E 2, is the AI independently creative?

To what extent Dall E 2 is independently creative seems questionable to us. If one understands creativity as using imagination to create original ideas, then in our opinion, the answer is: No. Because Dall E 2 does not create original ideas. The AI creates interpretations within the framework of learned conditions. But not beyond these conditions. However, if one takes a particularly close look, one could detect a hint of creativity in the mishaps and mistakes of Dall E 2’s image creation.

Free use? Legal uncertainties

From a legal perspective, two questions are of particular interest in connection with Dall E 2 creations:

1. Is there an author, and does copyright thus arise in the Dall E 2 creations?

2. Does Dall E 2 touch the rights of the authors of the works from which Dall E 2 draws inspiration from?

Does copyright protection arise in Dall E 2 creations?

Under European legal tradition, copyright is linked to the “creator principle”; it does not require any particular creativity or “threshold of originality” but at least an individual intellectual creation by a human being. Even if Dall E 2 is denied independent creativity and regarded more as a tool, it is clear that it the AI and not the person entering the text who creates here.

Thus, copyright protection is ruled out under the current legal situation. Similarly, the European Patent Office refused to register the ownership of the AI Creativity Machine DABUS for a patent because only a human being could be the inventor. On copyright law, U.S. courts also ruled in 2014 in the case of the famous “monkey selfie” that only a human being can be considered the author and owner of copyrights – the photographer who handed the camera to the macaque for his selfie thus came away empty-handed.

AI images for all?

Are all creations of a non-human “author” like Dall E 2, automatically in the public domain? At first glance, yes. OpenAI, in line with its philosophy, does not attach any additional legal conditions to the use of the creations.

As an interim result, neither the AI nor the entering human can claim copyright protection on the Dall E 2 works. Of course, this also brings the problem that these works are difficult to commercialize: If one wants to sell them to customers as part of more extensive work, for example, a catalogue or a website, their usage can hardly be restricted. Finally, there are no claims for injunctive relief or damages under copyright law.

But aside from commercial exploitation – does this now mean that creations by Dall E 2 may be used without restriction?

Where does Dall E 2 get its pictures from?

Claims by the owners of the underlying works that Dall E 2 “learns” from must also be considered. The image database Getty Images recently announced that it would no longer accept Dall E 2 creations, citing as the reason unaddressed rights issues related to the underlying images and metadata used to train these models.

It is initially not clear where the AI obtains all the works from which it “learns”. Are they all in the public domain, or are licenses taken? Or is this a case of “scraping”, i.e. automated “grazing” of the Internet without the consent of the rights holders? And further, even if the AI is was legally given access to the underlying works, it is still not clear whether the use by the AI, namely, the machine-based processing to “learn” a style, is permissible. Plaintiffs in the U.S. have jumped on this very point: Here, authors of works are suing the companies behind the AI systems Stability AI and Midjourney by way of a class action.

Enough distance from the “inspiration”?

In addition, there is still the “blackbox” problem: the “output” is uncontrollable. How is it ensured that Dall E 2 does not take “too much” inspiration or straightforwardly copy parts? First, it is already unclear on a factual level how far Dall E 2 has been “inspired” by existing images and how many components of existing works are used, copied, or “recreated”. There is no way to trace this.

But even if quantification is possible, the question remains; how much is too much? A few pixels? A figurative, incidental component of an image? An essential component? This always requires a legal evaluation, under a case-by-case analysis. The legal situation is clear only insofar as there is no copyright protection for specific ideas, methods or styles.

The above-described specification “hyperrealism” is therefore just as little problematic as, for example, the specification of a “Dalí style” or “pixel art”. Copyright always protects only one concrete form of expression. In the case of parts of a work, however, this is precisely where problems arise. “Inspiration”, similarities, and adoption of a style is OK– the adoption of works, or parts of them, is not.

Until recently, the legal standard, at least in Austria and Germany, was that in any case, a use is legitimate if the older work “completely fades” against the background of the new one.

In the CJEU’s 2018 decision “Metal on Metal” (in the area of music sampling), the standard is seen as even stricter: The new work is always “dependent” (requiring the consent of the author of the older work) whenever the older work is still “recognisable”. Whether this legal standard now also applies to graphic works is however still disputed.

The other existing exceptions to copyright law (so-called “barriers”: e.g. private copying, caricature, pastiche) are also unlikely to apply to most forms of use of Dall E 2.

This means that whenever Dall E 2 “recreates” significant parts of a copyrighted work, it is probably not a “free” adaptation but a “dependent adaptation”. This, in turn, would actually require the consent of the author of the underlying work before it could be distributed or reproduced. This means that any non-private use, especially any distribution, carries a certain risk that rights holders to one of the “original” works will come forward with claims – which is why databases such as Gettys do not currently take on this risk.